Like the amygdala or cortisol before that, Heart Rate Variability or HRV is an important psychophysiological concept that has begun to suffuse our cultural understanding of ourselves and bodies and minds. HRV research has completely skyrocketed in the past 20 years with new discoveries published about it every single day.

If you go to my favorite website for scientific information, Google Scholar, and type in HRV … you get 11,600 studies coming back … since January 2022!!!! Also, I think if you read the titles of the very first results that come up, you’ll get a sense of the wide-ranging import of HRV.

For the uninitiated, it’s confusing how HRV could be associated with so many important things.

Before we dive into the how or why, let’s start with the what: put simply, HRV is the differences in the speed of our heart beats. Put even more simply, high HRV happens when our heart beats fast when it needs to and slow when it needs to. When our heart doesn’t beat fast when it needs to be or slower when it needs to slow down, there isn’t much variability, and we have low HRV. When we breathe in, our hearts speed up; when we breathe out, our hearts slow down (which is why taking a longer exhale is calming). A heart that changes in this way with our breathing has high HRV; a heart that doesn’t change in this way has low HRV.

It actually takes a few times to really get what HRV is, so let’s talk about from a few other angles.

First, let’s distinguish heart rate from heart rate variability (HRV) if it’s not already clear. Heart rate is simply how fast your heart is beating in any given minute (or time period). HRV is the amount of difference or variability in those rates of heart beats. The main reason this is a little confusing is that we correctly think that a low heart rate (at rest) is a good thing ... but it’s high HRV that we want. It’s not really confusing if you just remember that you want a low resting heart rate and high HRV :)

A little more nuance that helps clarify these terms comes from the researcher (and lovely human being) Dr. Fred Shaffer: “the heart is not a metronome.“ Our heart doesn’t beat at 62 beats per minute (bpm) like our Fitbit is telling us … If our heart beat at one rate all of the time, we would likely be extremely sick. That 62 bpm is an average (a deceptively misleading statistic all around). Your heart may actually be beating at 72 bpm on your in-breath and then 52 bpm on your out-breath and so yes, the average is 62 bpm. But the point is that our hearts have a lot more variability than we think and that resting heart heart is really only one part of the story.

This last explanation is for the nerds (to which I would self-identify) … HRV is technically measured by the waveform produced by your heart as seen on an ECG. Each part of the heart waveform represents the beat of the heart (this would correspond to the action of the atria and ventricles). The top part is called the R as you can see below (it represents the contraction of your ventricles and when you can feel your heartbeat you are detecting the R spike often 200 milliseconds after it actually occurs) … The distances between R spikes is measured in milliseconds (828 … 845, etc. below); HRV is measured through the millisecond time differences between the R - R intervals.

Now you know what HRV is and hopefully one of those explanations landed for you. I think I can guess a next natural question that could use confirmation … Is high HRV good?

YES. I’m not going to laundry list this since there is just so much research associating HRV with cardiovascular health, risk of dying from a heart attack, severity of bowel disease … to how likely a sick baby is to survive … to having depression, PTSD, to how much you worry … to how compassionate you are and how good you are at recognizing others’ emotions … to how well you’ll do in exposure therapy … to how well you do at your sport or in a musical performance …

OK that was a little laundry listy, but it really is mind-blowing how much HRV represents … in fact, many people (including myself) consider HRV the first biomarker in clinical psychology. A biomarker is a measure in your body that gives you critical information; medicine is of course full of them ~ e.g. A1C tells us our average blood sugar over a 3 month period and guides treatment. Psychotherapy has never had biomarkers until HRV (which isn’t perfect, but I believe will become more specific over time); knowing someone’s HRV, for example, helps me predict how well they will be able to do with challenging therapeutic interventions and how much emotional resilience they may have that day.

How can HRV predict all of these diverse and important facets of physical, mental and emotional life? It can seem like snake oil until you understand some basic physiology …

Remember how I said the heart speeds up when we breathe in and slows down when we breathe out (the technical term for this is Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia)? And do you remember from a previous post that the Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS; through the Vagus Nerve) is like the brake pedal of our Autonomic Nervous System (ANS)?

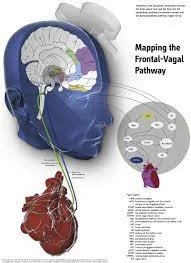

So now we can put together some interesting ideas: the reason our hearts slow down when we exhale is because our PNS (or Vagal Brake, remember?) activates or puts on the brake; when we inhale the brake (PNS) releases which allows for the heart to speed up. Notice how I’m not talking about the Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS)? That’s because the speeding and slowing is mostly about the PNS or our Vagal Brake.

Thus, HRV is mostly a function of the PNS. That means that HRV measures the strength of the PNS. If you remember in a previous post that a poor brake or an underpowered PNS is implicated in many if not most of the conditions for which people come to therapy, then you’ll begin to understand why HRV can be seen as a psychotherapeutic biomarker.

Even if HRV is a measure of PNS or Vagal functioning, how is it correlated with so many different aspects of life like cognitive ability or depression that are not directly related to the organs that the ANS innervates? Keep in mind that the ANS is actually directly connected to the brain (remember the Neurovisceral Integration Model from a previous post?) though the Vagus Nerve.

I like to think of the heart - brain connection in a simple way: a calm heart (or body) regulates the brain and a calm brain regulates the heart. If you remember the previous post when I discussed the Neurovisceral Integration Model, the most exciting heart - brain connection to me is that having high HRV is associated with a strong Prefrontal Cortex which can then inhibit the strong emotions and resulting over-thinking originating from the amygdala.

None of this would be particularly worthwhile unless we could improve it. Amazingly, we can deliberately up-train our HRV (and thus the strength of our brake, the PNS system or the tone of the Vagus Nerve) through HRV biofeedback. It’s not the only way; exercise in particular will improve your HRV as will quality social interactions / relationships, certain dietary patterns, temperature changes / challenges, meditation … but HRV biofeedback is specifically designed to do this, will create big changes faster than other methods and is easy to do with the help of a professional biofeedback therapist or even on your own. However, if HRV biofeedback is just one class with one grade, you can’t really raise your overall GPA without doing the other things that are healthy for your body and mind.

I know all of this physiology can be confusing, so here are my take-homes:

HRV is the range of the heart’s speed

It’s a very, very good thing to have more HRV

High HRV means your PNS is working great, low HRV being the opposite

Having high HRV will help you regulate your emotions amongst many other things

HRV can be trained and improved through, amongst other strategies, HRV biofeedback

Congrats, you made it through the background / technical articles! They will serve as vocabulary building for a new language that will unlock an understanding of your psychophysiology that I hope will deepen your understand and appreciation for who and what you are.

Reference:

Shaffer, F., McCraty, R., & Zerr, C. L. (2014). A healthy heart is not a metronome: an integrative review of the heart's anatomy and heart rate variability. Frontiers in psychology, 5, 1040.