As a practicing psychologist of 10+ years, teaching this simple relaxation technique has been my most shared tool; I’d venture to guess that this is true for a majority of mental health professionals. It seems so simple and basic, but if I only had three minutes to help someone, this would be my choice [just so I don’t bury the lead, the technique is down below in case you’re not feeling like reading the scientific background].

I remember when I was in graduate school for clinical psychology, I was surprised how this technique seemed to be one of the mainstays of mental health interventions … until I started to understand the underlying the psychophysiology.

On the surface, it’s pretty simple: if you breathe with your diaphragm, more slowly, not too deeply and with a prolonged exhale, you stimulate your Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS; i.e. the vagal brake). And that calms you down.

It also just makes sense if you are a careful observer of how people use breathing in relation to stress … no doubt you’ve sighed when you’re stressed or frustrated, you’ve likely told someone to “take a deep breath” or thought “I just need to breathe right now, it’ll be OK.“

If one does a deep dive into the literature, the story gets more complex, and I’ve not found any studies or series of studies that have convinced me that one way of breathing is always better than another. Why might that be the case? In addition to their just being a limited number of studies examining comparisons of breathing methods (not exactly profitable to any particular industry), there’s also a lot of nuance when one asks what technique is “better.” Better for who and what? People with COPD, for a healthy person trying to relax, for someone who chronically over breathes vs. doesn’t, for the outcome of physiological changes vs. perceived relaxation vs. respiratory efficiency vs. an increased internal (or interoceptive) awareness of breathing processes?

So, there’s not one answer for everyone and I’d be skeptical of anyone selling a breathing method as a cure-all. This can happen with certain breathing methods; my conclusion would be that they could all be helpful for certain things at certain times for certain people. However, I do feel very confident in the method I’m going to describe to help most people engage their relaxation response regardless of how good of breathers they are.

Based on my review of the evidence and my clinical experience (though, as with everything I teach, this should and will change with new evidence), breathing to engage relaxation or PNS involves the following (scientific rationale included):

1. Breathing slowly (ideally around 6 breaths per minute, 4 seconds in, 6 seconds out) and not too deeply.

One effect of slow breathing at or around 6 breaths per minute is that it syncs up our heart rhythm with our breathing rhythm and produces an effect called Respiratory Sinus Arrythmia (see below) …

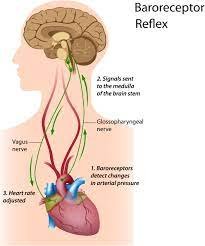

… that has the effect of stimulating something called the Baroreceptor Reflex, which helps us control our blood pressure and also improves the functioning of our PNS … As I’ve discussed in previous posts, this seems to help emotion regulation centers of the brain …

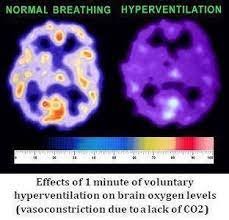

… not too deeply … wait, what?! Doesn't your mom and your therapist tell you to just take a deep breath to relax?? As it turns out, breathing deeply can actually maintain a problematic cycle of overbreathing or hyperventilation; put simply, when we breathe too deeply, we breathe out too much carbon dioxide (CO2). We actually need a certain level of CO2 because it helps our O2 release from hemoglobin cells (i.e., it helps our tissues get oxygenated). So, if we’re breathing too deeply, we’re getting rid of too much CO2 which can have some major consequences on our overall O2 levels … check out this visual of our brain oxygenation with normal vs. overbreathing (or hyperventilation) …

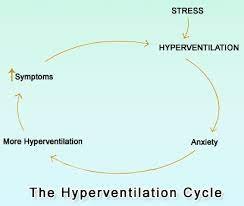

Also, breathing deeply can maintain a cycle of stress & hyperventilation …

2. Engaging your diaphragm muscle and reducing other breathing-related musculature

Breathing with your diaphragm (see below) increases respiratory efficiency (meaning you don’t have to breathe as much or quickly to get the same benefit) and creates greater autonomic / physiological relaxation. This compares to breathing with your chest or shoulder / clavicular / neck muscles which, as I understand, increases sympathetic arousal, and can maintain psychophysiological breathing problems.

3. Exhaling (through the mouth with pursed lips) a little longer than the inhale (through the nose)

OK this is my recommendation with the least amount of science behind it. There have been several studies showing no differences or even superiority on some autonomic measures with an even exhale - inhale ratio (for example 5 seconds in, 5 seconds out). However, in my clinical and personal experience, there is something emotionally calming about an extended exhale. So I’m going to stand by that until it’s shown to be untrue (which it hasn’t to my knowledge).

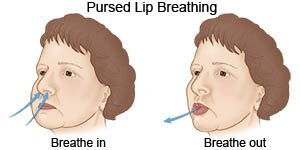

In particular, I love the pursed lip breathing technique for an exhale (see the picture below to illustrate the pursed lips) … I’ll describe it below, but it’s essentially breathing out with nearly closed (or pursed) lips; it does a great job of slowing the exhale and it’s regularly taught to patients with severe asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). As I mentioned, it also helps regulate emotions during times of high stress (much more effectively than sighing in my experience, though Dr. Andrew Huberman may beg to differ) …

In terms of the mouth vs. nose issue, I’d refer you to James Nestor’s excellent book Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art; he does an excellent job making the case for nose-only breathing. To summarize it simply, the nose was made for breathing: it filters out more bacteria, it provides more air resistance thus slowing the breathing and it warms the air. I’m convinced that breathing in through your nose makes a whole lot of sense, though I’d have to be convinced that exhaling with one or the other really matters. There are really interesting data about how consistent mouth-breathing changes the shape of your face as well as your dental health; however, that’s out of my field of knowledge so I’ll leave that to others to explain.

I’ve probably taught thousands of people to breathe using this 3-step technique that’s described below ~ people of all ages with different levels of health, cultural / linguistic background and stress-related breathing problems. Below is exactly what I teach these days; I stand behind anyone using this method for 10-20+ minutes per day as a safe, tolerable and easily-learned way to breathe for relaxation. While learning to do this on your own may not be the same as getting training from me in the office with realtime feedback about your breathing, if you are able to get the method down the benefit will be the same.

Here are the instructions:

STEP 1:

Put one hand on your stomach and one hand on your upper chest. Look down at your hands or in a mirror and your goal is to breathe only with your stomach. The hand on your stomach should be moving out when you inhale and back in when you exhale; the hand on your chest shouldn’t be moving. You also won’t need to breathe as deeply and you can allow yourself to breathe a little more lightly and naturally; the increased efficiency of diaphragmatic breathing will get your body more than enough oxygen with less effort. Once you’re more comfortable with that technique, move on to step 2 …

STEP 2:

Now, make sure that you are breathing in through your nose, and out through your mouth. But when you exhale, put your lips together as if you were going to try to flicker a candle but not blow it out or you were trying to blow a bubble. This is called pursed-lip breathing and it will help you slow down your exhale. Go ahead and practice this with diaphragmatic breathing.

STEP 3:

After you feel comfortable combing diaphragmatic breathing with nose-inhale and pursed-lip exhale, the final step is to pace your breathing. When you breathe in through your nose, count to 4; when you breathe out through your pursed lips, count to 6. There are plenty of pacers or websites you can use, or you can simply count in your head, think of words or music that lasts that amount of time or use the second hand of an old-fashioned wall clock. If you are having a hard time with the 4 : 6 ratio, I would start on 3 : 5 (i.e. 3 seconds for the inhale, 5 seconds for the exhale) and work your way up to 4 : 6.

Simple as that. I’d suggest that doing an intentional practice of this breathing method for 10+ minutes per day (ideally 20) will improve some aspect of your life if you have any degree of stress. Carving out a time and space for this practice and mindfully paying attention to your breathing without doing other activities will likely help the most; but if it’s a choice between doing it while you’re watching Netflix and not doing it, I would still think there would be benefit (Netflix hasn’t funded this study yet to my knowledge; yes, I actually do this sometimes!). Another question I get a lot: should be breathing this way all of the time? Probably not; breathing to fit the situation is likely a good idea. Though ideally you’re breathing with a little more awareness during the day and perhaps a little slower and with your nose more. I would believe that breathing this way throughout your day could prevent stress-related breathing problems and other forms of physiological anxiety.

My hope is that this 3-step process for breathing for relaxation will be beneficial to you or someone you know … the more regulated human beings there are in the world, the better.

References:

Laborde, S., Allen, M. S., Borges, U., Dosseville, F., Hosang, T. J., Iskra, M., ... & Javelle, F. (2022). Effects of voluntary slow breathing on heart rate and heart rate variability: A systematic review and a meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 104711.

Laborde, S., Allen, M. S., Borges, U., Iskra, M., Zammit, N., You, M., ... & Dosseville, F. (2022). Psychophysiological effects of slow‐paced breathing at six cycles per minute with or without heart rate variability biofeedback. Psychophysiology, 59(1), e13952.

Lin, I. M., Tai, L. Y., & Fan, S. Y. (2014). Breathing at a rate of 5.5 breaths per minute with equal inhalation-to-exhalation ratio increases heart rate variability. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 91(3), 206-211.

Ma, X., Yue, Z. Q., Gong, Z. Q., Zhang, H., Duan, N. Y., Shi, Y. T., ... & Li, Y. F. (2017). The effect of diaphragmatic breathing on attention, negative affect and stress in healthy adults. Frontiers in psychology, 874.

Steffen, P. R., Austin, T., DeBarros, A., & Brown, T. (2017). The impact of resonance frequency breathing on measures of heart rate variability, blood pressure, and mood. Frontiers in public health, 5, 222.

Szulczewski, M. T. (2019). Training of paced breathing at 0.1 Hz improves CO2 homeostasis and relaxation during a paced breathing task. PLoS One, 14(6), e0218550.