I’ve talked a fair amount about paced, diaphragmatic breathing at 6 breaths per minute. Hopefully I’ve addressed the science behind slow breathing and using your diaphragm, but what’s the deal with 6 breaths per minute?

There’s actually a very simple way to answer that question: it is the breathing frequency that generally tends to create the highest Heart Rate Variability (HRV).

However, thanks to the pioneering work of Drs. Paul Lehrer and Evgeny & Bronya Vaschillo, we know that every person has their own ideal breathing rate that stimulates the highest HRV for them.

We could stop there, but I’ll go a bit more into the science behind the above statements. Much has been written on the subject of Resonance Frequency breathing (check out the references below if you want to deeply understand it), so I’ll summarize my understanding.

Many body systems regulate themselves through negative feedback loops ~ which means that there is a level the system likes to be at (i.e. homeostasis); when the system goes out of that range, some physiological feedback stimulates a correction that helps the system return to its programmed homeostatic range. The classic metaphor that’s used is that of a thermostat in a home: we want our houses at a certain temperature for comfort (which is a homeostatic range) and when it goes too high or too low, we kindly request our thermostats to automatically heat or cool to keep it in our programmed homeostatic range.

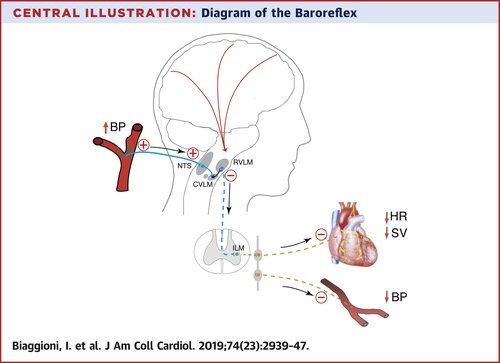

There are lots of examples of negative feedback loops in our body; a relevant one for us is called the Baroreflex system. We have cells in some of our most important arteries that receive information about how much the blood vessel is stretching; for example, if we start to get very stressed and our SNS kicks in and constricts our arterioles (lower hand temperature, remember?) … these stretch receptors sound the alarm that our blood pressure is increasing and starts a physiological process that reduces our blood pressure.

For any negative feedback loop, there is a way to create larger and larger fluctuations through a physics principle called Resonance. The way to create this resonance is by stimulating the system with the exact right frequency (…i.e. the Resonance Frequency). In many systems, resonance is not a goal; in fact, if you’re building a bridge, it’s something to strongly avoid! But if you want more of a system’s output, it’s a good thing; since we want more and higher HRV, Resonance is our friend.

So, if the goal is to create the largest fluctuations in the cardiovascular system (i.e. HRV), we simply need to find the Resonance Frequency. The most effective way to stimulate larger HRV is through breathing (though not the only way, rhythmically tensing your skeletal muscles 6 times per minute also produces some resonance) so our Resonance Frequency (RF) is the breathing rate that creates the highest HRV in each of us. Even though 6 breaths per minute tends to be the best guess for an RF for anyone; everyone has their own RF and it’s nearly always (for adults) between 4.5 breaths per minute (this is mine) to 6.5 breaths per minute.

Why does everyone have their own and it’s not just 6 breaths per minute for everyone? Simply put, we all have differently sized vascular trees (usually based on height and sex) which creates slight differences in the delay of our cardiovascular / baroreflex systems.

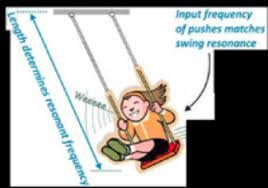

I love the metaphor that the expert biofeedback educator Dr. Inna Khazan uses to help solidify the concept of RF … Imagine you are pushing a child on a swing … The goal is to create the largest fluctuations, i.e. the highest arc, to get maximal giggles & joy, right? You don’t want to push the kid too early or too late in the arc of the swing because it will disrupt the momentum which = less giggles :( So there’s one particular rate of pushing the kid that is going to be perfect to create the biggest swing and the happiest giggles; that particular frequency depends on the length of the swing chain and the size of the kid.

In this metaphor, the kid giggling is HRV (we want more), the adult pushing is the breathing frequency (we want the exact right frequency for resonance) and the length of the chain is the slight differences in different people’s cardiovascular systems (explaining the slight differences in the individualized breathing rate, or RF).

While there is some discussion in the field about this, the consensus at this point seems to be that RF, if assessed accurately, remains the same throughout your entire adulthood.

So, how do you find out your Resonant Frequency (RF)? It’s easy to do if we’re together in my office with my biofeedback equipment, but it’s also possible to do at home. Both Dr. Inna Khazan and Dr. Leah Lagos both have books (linked if you’re interested) that go through their own methods that use at-home HRV devices. However, the basics of any RF assessment include:

Breathing at 6.5, 6.0, 5.5, 5.0 & 4.5 breaths per minute for 2 minutes each with 1-minute breaks in between.

For each data point, right down your HRV and how comfortable you felt at each pace.

The breathing frequency with the highest HRV and comfort is your likely RF.

Can you do it without measuring your HRV? Sure … you’ll probably have a lower chance of being accurate, but you could just make a decision based on how you felt during each pace.

How do you measure your HRV on your own? Well, you’ll need a device (Kyto, HeartMath, CorSense, Polar H7 or the more recent ones) and an app that goes with your device (Kyto, CorSense and Polar H7 all go with both Optimal HRV and Elite HRV ~ both of these apps provide specifics on what aspect of HRV you’re actually measuring, RMSSD would be my choice of what HRV measures to index as it gets at vagal tone more than many measures; HeartMath has its own app called InnerBalance that gives you a “coherence score“ which is their proprietary HRV score; other measures of HRV like smart watches etc. will give you an “HRV“ score which is also proprietary and difficult to interpret, but better that than nothing when trying to find your RF on your own). I’m certainly not associated with any product, but I have a strong preference for devices that tell me objective, non-proprietary, measures of HRV that I can compare to others based on scientific research (vs. what the app tells me my score means). However, the message here is to work with whatever you’ve got!

Knowing your RF is a gift that you’ll have throughout your life. However, whether you are able to find out your RF or you just choose 6 breaths per minute, you are very likely to benefit from this powerful technique of intentional breathing that syncs up your heart rhythm, blood pressure and respiratory systems & invites your whole system into a state of psychophysiological regulation.

Reference:

Lehrer, P. M., Vaschillo, E., & Vaschillo, B. (2000). Resonant frequency biofeedback training to increase cardiac variability: Rationale and manual for training. Applied psychophysiology and biofeedback, 25(3), 177-191.

Shaffer, F., & Meehan, Z. M. (2020). A practical guide to resonance frequency assessment for heart rate variability biofeedback. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 14, 1055.

Shaffer, F., Moss, D., & Meehan, Z. M. (2022). Rhythmic Skeletal Muscle Tension Increases Heart Rate Variability at 1 and 6 Contractions Per Minute. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 1-10.

Vaschillo, E. G., Vaschillo, B., & Lehrer, P. M. (2006). Characteristics of resonance in heart rate variability stimulated by biofeedback. Applied psychophysiology and biofeedback, 31(2), 129-142.